After I released the first version of Criterion.rs, (a statistics-driven benchmarking tool for Rust) I was asked about using it to detect performance regressions as part of a cloud-based continuous integration (CI) pipeline such as Travis-CI or Appveyor. That got me wondering - does it even make sense to do that?

Cloud-CI pipelines have a lot of potential to introduce noise into the benchmarking process - unpredictable load on the physical hosts of the build VM’s, or even unpredictable migrations of VMs between physical hosts. How much noise is there really, and how much does it affect real-world benchmarks? I couldn’t find any attempt to answer that question with real data, so I decided to do it myself.

tl;dr: Yes, there is enough noise to make benchmark results unreliable. Read on if you want to see the numbers.

In this post, I benchmarked on Travis-CI, but I don’t mean to single them out, they’re just the cloud-CI provider that I’m most familiar with. To the best of my knowledge, they don’t claim that their service is suitable for benchmarking.

Methodology

Before I can test the effects of the cloud-CI environment on benchmarks, I need

some benchmarks. I opted to use the existing benchmark suite of Rust’s

regex library, because it’s a well-known,

well-regarded and high-performance codebase. Specifically, I used the “rust”

benchmark suite. The regex project’s benchmarks use Rust’s standard libtest

benchmark/test harness.

I ran the benchmarks in pairs, as suggested in this post by BeachApe. However, that post suggests running one benchmark with master and one with a pull-request branch - all of my benchmarks were done with the same version of the code to prevent changes to the code from affecting the results. For the cloud benchmarks, each pair was run in a separate build job on Travis-CI.

I wrote a script to run 100 such pairs of builds on an old desktop machine I had laying around, and another to run 100 Travis-CI builds by editing, committing and force-pushing an unused file, then downloading the resulting build log. Note that I did edit the Travis build script to only perform the necessary compilation and benchmarking, to avoid using more of Travis-CI’s resources than was necessary. A few of the resulting log files were damaged and were replaced with log files from new builds at the end. There were a number of occasions where parts of the logs from Travis-CI were missing or corrupted and I am not certain that I found all of them.

Each pair was then compared using cargo benchcmp and the percentage differences were extracted with more scripts.

The pairwise benchmarking approach has a few advantages. First, by running both benchmarks on the same physical machine (for local benchmarks) or the same build job (for cloud benchmarks), all effects which are constant for the length of a benchmark pair can be ignored. This includes differences in the performance of the physical hosts or differences in compiler versions, since we’re only looking at the percentage change between two consecutive benchmarks. Using the percentage differences also controls for some benchmarks naturally taking longer than others.

Results

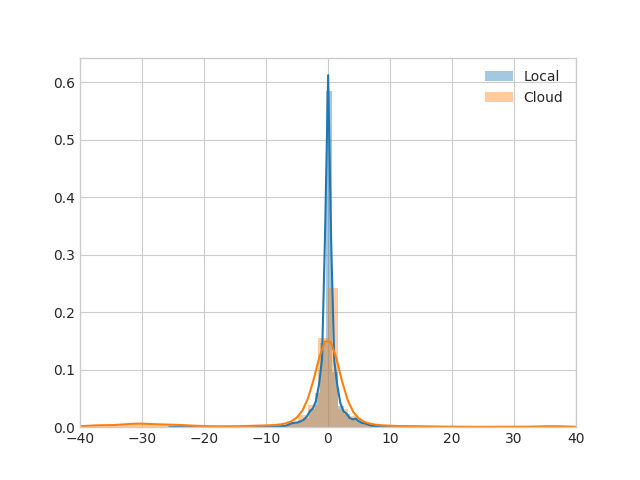

As you can see from the above chart, the cloud benchmarks do indeed show more noise than the local benchmarks.

All numbers are in units of percentage points representing the percentage difference between the two benchmarks of a pair:

Local:

mean: 0.0315897959184

min: -24.6, max: 22.18

std. dev.: 2.11411179379

Cloud:

mean: 1.42961542492

min: -99.99, max: 3177.03

std. dev.: 72.1539676978

Levene's Test p-value: 1.97E-49

Note that there were four benchmark results in the cloud set with percentage differences greater than 10,000% which I’ve removed as outliers. Those were not included in the calculations above; if they were included the cloud numbers would be substantially worse. I opted to remove them after inspecting them and finding inconsistencies in those benchmark results which lead me to suspect that the logs were damaged. For example, one benchmark shows the time for each iteration increased by more than 200x but the throughput for the same benchmark appears to have increased slightly, rather than decreased as one would expect.

Additionally, manual inspection of the comparison results shows that sometimes multiple consecutive benchmark tests within a single run of the benchmarks all differ from their pair by a large and consistent value. This could indicate something is slowing down the build VM by a significant degree and persisting long enough to affect multiple benchmark tests.

Conclusions

The greatly increased variance of benchmarks done in the cloud casts doubt on the reliability of benchmarks performed on cloud-CI pipelines. This confirms the intuitive expectation.

To be clear; this doesn’t mean every benchmark is wrong - many of the comparisons show shifts of +-2%, roughly similar to the noise observed in local benchmarks. However, differences of as much as 50% are fairly common with no change in the code at all, which makes it very difficult to know if a change in benchmarking results is due to a change in the true performance of the code being benchmarked, or if it is simply noise. Hence, unreliable.

It would still be useful to have automated detection of performance regressions as part of a CI pipeline, however. Further work is needed to find ways to mitigate the effects of this noise.

One way to reduce noise in this system would be to execute each benchmark suite two or more times with each version of the code and accept the one with the smallest mean or variance before comparing the two. In this case, it would be best to run each benchmark suite to completion before running it again rather than running each test twice consecutively, to reduce the chance that some external influence affects a single test twice.

A simpler, though more manual, method to accomplish the same thing would be to run the whole benchmarking process in multiple build jobs. In that case, before merging a pull request, a maintainer could manually examine the results. If a performance regression is detected by all of the build jobs, it’s probably safe to treat it as real rather than noise.

It is also possible that different cloud-CI providers could make for less noisy benchmarking environments, though I haven’t measured that.

All of the data and analysis scripts can be found on GitHub

Thank you to Daniel Hogan, for reading over this post and giving me a great deal of useful feedback. I’d also like to thank Andrew Gallant (@burntsushi) and co. for creating both the regex crate and cargo-benchcmp.

Addendum: Why libtest and not Criterion.rs

I opted to use Rust’s standard benchmarking tool rather than Criterion.rs because there are no large, well-regarded projects using Criterion.rs to perform their benchmarks at present.

I don’t know whether using Criterion.rs would change these results or not. Criterion’s analysis process is different enough that it might, but until I have data one way or another I intend to advise users not to trust cloud benchmarks based on Criterion.rs.