Welcome back to my series of posts on the recipe-management software I’m building. If you haven’t been following along, you’ll probably want to start at the first post. This isn’t so much a tutorial series like my posts on raytracing, just me writing about whatever’s on my mind as I build out my vision of what a recipe manager should be.

Progress

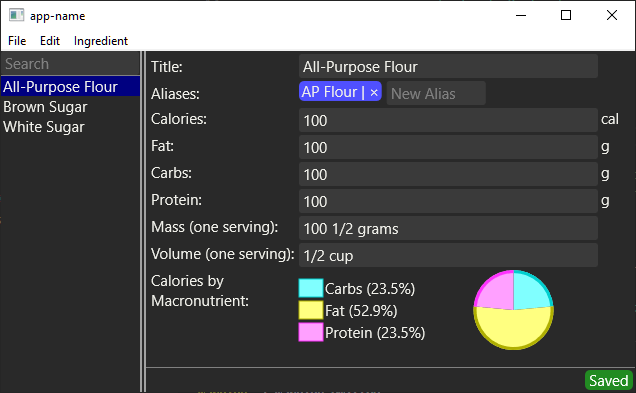

In the last post I finished building the ingredient editor itself (at least for now). Since then, I’ve gone one step up and added a searchable list of ingredients.

As you can see, there’s a searchable list of ingredients, as well as a menu. That double-line widget is a split-pane; it can be dragged back and forth to expand the list of ingredients. I was planning to write my own split-pane, but it turned out Druid actually did have the component I needed. The list filters in realtime (though the code backing it is pretty dumb at this point) and there’s even context menus on the list to allow the user to create and delete ingredients. I’ve also fixed a bunch of bugs and minor user-experience flaws (for example, if you leave text in the Aliases field it will be automatically added to the list of aliases and saved when you tab away to another field, rather than just being lost).

Naturally, this means that the backend code is scanning and opening all of the ingredient files. Which leads me to…

Wow, async-std is fast!

I wrote a totally naive implementation of loading all of the ingredient files in parallel using async-std, and decided to see how fast it was. Pretty fast, as it turns out - it can load, parse, and collect 500,000 test files in ~45s, for a throughput of a bit over 11k/second.

OK, yes, 11k records/second using all 4 cores/8 threads of my ~5-year-old gaming machine, loading from SSD might not seem that impressive. I’m sure that if I had 8 threads querying the same data from a sqlite database it could go faster. Still though, consider how I’m storing the data - one record per file, in TOML files rather than a structured binary format. I’m deliberately sacrificing performance for the ability to read the records without special tools. In that context, 11,000 records/second is darned solid performance, and the performance/effort ratio is awesome. Here’s my entire code for parsing these files:

I’m using the walkdir crate to traverse the directory and spawning an async-std task for each file. It pushes each spawned task into a FuturesUnordered collection (because I don’t care what order they complete in) and collects that into a vector. It’s almost exactly the same code as I would write if I were doing it entirely sequentially - the only difference is the presence of the async/await keywords and the fact that I’m pushing spawned futures into a FuturesUnordered and collecting to a Vec instead of just pushing the Results into a Vec directly.

Incidentally, this is one of the things I love most about the Rust ecosystem - it’s so often possible to get really great performance for barely any effort because all of the clever parts were already written by someone else. I just have to glue them together and watch them go.

I’m not sure whether I’ll even bother building a loading screen, considering this performance. It’s going to take me an awfully long time to accumulate enough recipes for it to take any appreciable time to load at all. Maybe parsing recipes will take more time than parsing ingredients?

I used to be skeptical about async/await. It took a lot of work for the compiler team to build, a lot of work for other teams to build the reactors, and there’s still the confusing ecosystem-split between async-std and tokio. I thought that async/await was mostly only useful for bleeding-edge networking performance and I figured that most services would be better off with the simple approach of forking a thread to handle every request. I was totally wrong on how much effort async/await adds, and consequently I was wrong about the rest of it as well.The ecosystem fragmentation is still a problem though; I hope that can be improved going forward somehow.

Although I did notice that if I remove the spawn call from that code and just push the

load_ingredient future directly into the FuturesUnordered it goes way slower (160s instead of

45s) and I don’t really know why? Let me know if you do.

Even more Druid

If you’ve been following this series, one of the things I’ve brought up a few times is that I’m not sure how intrusive Druid’s widgets should be on the application’s data model. After five weeks of working with Druid, I think I’m starting to get a better sense of the answer to that.

As usual, my example is my autosave timer widget. You can see it in the screenshot above, the “Saved” text in the corner of the window. It switches between Saved, Failed (meaning there was a file system error or similar on attempting to save the data), Invalid (the data in the editor can’t be saved because it’s invalid) and Ticking (which shows an animated timer counting down to when it autosaves).

When I built it, I figured that the state of the timer shouldn’t intrude into the application’s data model, but instead should remain compartmentalized into the widget itself. Instead, there was another component which observed changes to the application model and sent Commands to the widget to tell it to start ticking, or that the save had failed, etc. Druid’s developers advised me that using Lenses was more idiomatic than relying on Commands, but that approach seemed more complex to me for no particular gain.

In adding the ability to load multiple ingredients, though, I’ve found the limits of my initial approach and converted it to use lenses and keep the timer state in the application model instead.

With the original implementation, when I clicked around on the list of ingredients, each ingredient that I loaded would trigger an update through Druid. That makes sense, the data in the model has changed and so it needs to be rendered. The problem is that there’s no distinction between the user loading new data and the user editing the data directly, so my code would detect each load as a change and start the auto-save timer ticking. Now, I could have fixed that by having it send a “wait, no, ignore that last change, that was loading new data” command after every load, but then I have to remember to do that, and if I forget then the compiler can’t help me. By baking the timer state into the application model, when I build the model object the compiler forces me to specify what state the timer should be in. I still think it’s more complex than my first approach, but it turns out that complexity was there for a reason.

The solution I’ve settled on for now is as follows. I have a model structure for the ingredient

editor, which contains the text strings, the nutritional information, etc. - all the things which

“logically” part of the ingredient editor’s model. Then, as a wrapper on top of that, I add a

EditorState<T> model struct that stores the ingredient editor’s model and the timer state, and an

Editor widget which handles most of the logic for the autosave - it detects changes to the

underlying editor data and starts the timer ticking, receives Ctrl-S commands if the user chooses

to save early, handles most of the code to submit the saved data back to the backend to be saved

asynchronously, and so on.

Then the all-ingredients view contains an EditorState<IngredientEditorModel>. When it loads data

from the backend, it can call

EditorState::loaded(IngredientEditorModel::from_backend(ingredient)) to get back a state where

the timer will read “saved”. When the user creates a new ingredient, it calls EditorState::new

and gets one in the invalid state - which is appropriate because the user hasn’t filled in enough

data to save yet. The code change in making this switch was pretty large and introduced a number of

bugs, but I think I’ve got them all ironed out. And, yes, there’s even some lenses - I use a lens

to automatically set the timer ticking if the editor contents change without resetting it when the

timer itself changes.

In other Druid news, I’ve had a small patch accepted into Druid to allow the user of the Split widget to set the minimum size for each side separately, rather than assuming one minimum size would work for both sides.

Conclusion

The all-ingredients editor is pretty much finished at this point. Now that I can edit and save ingredient data, the next thing is to start working on the recipe editor itself. All of the widgets and design ideas I’ve built up so far for the ingredient editor will come in handy for the recipe editor, but there are still plenty of problems to solve.

I had a bunch of vacation time at work that I needed to use up. What with the whole pandemic situation (and the blizzard raging outside my window right now - Oh, Canada…) there’s not much else to do with it at the moment, so I’m taking a week off work and I plan to spend a bunch of time on the recipe manager. Can’t leave the house anyway, might as well get coding.