Something you might not know about me is that I’m an avid home cook. As such, I like to experiment in the kitchen, improvise new recipes, and modify existing ones. I also track my calorie and macronutrient intake. I have software tools for this, but I don’t like them and eventually I got fed up and decided to write my own.

I also thought it would be interesting to try working with the garage door up and writing more publicly about what I’m working on, so this is part one of an ongoing series where I do just that. This isn’t going to be a tutorial series like I did for raytracing and path tracing, just whatever I’m thinking about or working on at the time.

Project Goals

A lot of people have trouble with developing software from scratch, starting with a blank repository. It can be difficult to decide where to start, to pick one manageable piece out of the complexity of the finished project, or even to decide what project to build in the first place.

For my part, I generally have more project ideas than I have the time or energy to build. I usually let them sit in the back of my mind, simmering away on the back burner as it were, for months or even years before I commit to building them. This serves two useful purposes. First, most of the less-interesting project ideas fade away and are forgotten - a helpful filter to weed out the weaker ideas. Second, the ones that don’t usually get stronger in the process - I’ll find myself thinking about the project in my downtime - in the shower, on walks, and so on - and come up with further ideas about what I want the project to be, what implementation or design decisions would make sense, that sort of thing. I write these down to save them for if and when I finally do commit to building it.

By the time I do finally start building the project, this means I usually already have a pretty solid idea of what I’m going for, the general shape of the design, major technology choices, and the rough order of operations. I start by figuring out the desiderata - what do I want in a $PROJECT?

In this case, what I want in a recipe manager/calorie tracker is:

- It should be wicked fast. I’m going to be using this live, while cooking. I don’t have time to wait for several multi-second page-loads per ingredient.

- It should be low-friction. See above. The app should do as much of the work for me as it can.

- It should be mostly usable with just the keyboard. It’s going to have a GUI, but this means things like tab-focusing need to work well. I’ll have a laptop in my kitchen when I’m using this app, and the trackpad is neither wicked-fast nor low-friction for me as the user.

- It should be local-first. Storing all data locally is key to achieving wicked-fastness. This also means I get to keep total control over my data, which is nice.

- It’s not necessary for the first version, but later on I’ll want to be able to sync data to other devices for backups and the like. I’d also like to be able to access it on my phone, so I can look at my recipes while at the grocery store.

These design principles lead pretty naturally to major technology choices:

- I’ll be using Rust. Rust is my first choice for pretty much everything anyway, but this project will benefit from Rust’s speed and light weight. I could probably build it in Java (certainly Java’s GUI toolkits are far better than Rust’s) but then I’d have to install a JVM and have it taking up a bunch of RAM and that’s a drag. So, Rust it is.

- Some of the ideas I have for minimizing friction will require custom widget rendering, so I’ve picked Druid for my GUI framework. It’s still quite unfinished, but it provides powerful tools for building custom widgets and Raph Levien and the other Druid contributors seem to share my performance goals.

- I’m not using a database. I’d originally considered sqlite - it’s fast, robust, small - on paper it’s exactly what I want for this project. But after thinking about it for a while I realized it would get in my way when it comes to implementing syncing. My data is relatively simple, so I’m going to store it as a regular folder full of regular text files - probably TOML, maybe some custom text format for the recipes themselves. This is handy in that I can implement a basic version of syncing just by storing the folder in Dropbox or something similar.1 Also, I can look up my recipes on my phone by opening them in the Dropbox app’s text editor until I get around to learning how to write Android apps. Down the line, when the time comes to implement real syncing, I’ll be able to build it on top of git, which is already optimized for text and will even give me a history of all my changes for free.

- I’m going to load all of the data at startup and keep it in memory while the app runs. This is a major simplification and performance optimization, especially for things like searching. I can build n-gram indexes and the like in memory while I load the data. It will cost some memory, but it’s just text, it won’t be that large. I’m not worried about startup time either - it can all be loaded in the background in parallel, and anyway SSDs are super fast.

- To keep the GUI fast and responsive, all of the heavy work will be done in the background. In particular, I’ll be using Rust’s async-await support with async-std as my reactor of choice.2

Any or all of these decisions might bite me later, but I have to pick something. Most of them I’m pretty sure about, but Druid is a particular risk - Druid describes itself as experimental, and it’s clearly missing a lot of features that would be required for a production GUI toolkit. I think for the most part I can work around those or provide my own custom widgets to fill in the gaps. Just to be safe (and for general architectural reasons) though, I’m going to try to build my code so that the GUI code isn’t too tightly coupled to the rest. That will limit the damage if I ultimately decide I have to replace Druid with something else. I expect breaking changes, but I’m sure I’m going to be maintaining this code occasionally for pretty much the rest of my life (like I have maintained my RSS reader3 ever since I wrote the first version back in university) so I’m OK with that.

When I’m doing side projects like this, I also generally try to pack as much learning and experimentation into these projects as seems practical. If I’m going to be spending my free time building something, I might as well be as efficient as I can and get as much value out of it as I can manage. In this case, the major areas of experimentation are using Druid, heavy usage of async-await with async-std (rather than a more normal thread pool like I would in Java) and writing this blog series.

When I’m building things for work, I usually don’t have the luxury of spending months thinking about a problem. On the other hand, work tasks are usually a lot better-defined - fix bug, add feature. For the bigger ones that aren’t so well defined - refactor this large section of code, make this app run automatically without needing as much tricky configuration by the user - I will still take the time to figure out what I’m building, though. I believe in building the right thing and building it the right way. Happily, I have an employer who tolerates me in this. Even at work, every once in a while I do get to think about a problem for a long time before I build it, and that’s when I do my very best work.

Order of Operations

The term comes from mathematics, but I’m often inspired by the ways that Adam Savage, in his build videos on Youtube, talks about how he thinks through his builds. It got me thinking about how I do my own.

When I’m building a program, I usually follow the data path. There’s usually a pretty obvious dependency tree - component A gets data from B gets data from C, which gets data from the user, or a data file, or a network service or whatever. I always start with one of the leaf nodes in that tree, the places where data enters my system. When I wrote my NES emulator, I started by hand-writing a iNES ROM parser. It wouldn’t make sense to have a CPU implementation with no ROM data to run it on. For TinyTemplate, I started with the template parser.

From there, I build something that builds on the part I just finished - like the memory access code that maps memory addresses in the NES’ 16-bit memory space to parts of the ROM. That then gives me more things I can build on, and I can continue until ultimately I have a working system.

These dependencies are always pretty soft, of course. As I build things out, I end up reaching places in that hierarchy where I don’t have all of the dependencies built yet. That’s fine. I can build out the CPU emulation without first finishing the graphics rendering, sound output, or controller input.

Of course, you don’t have to do it this way - you can always write artificial data to use in unit tests if you want to start with something higher-level. This is just how I do it.

For the recipe manager that is nominally the subject of this post, I’ll start with the ingredient editor.

The Ingredient Editor

I’ll need to have a database (in the sense of a collection of data) of all of the ingredients that I cook with and their nutritional values before I can start combining them into recipes. Several months ago I experimented with loading up the USDA food nutrition dataset to pre-populate this database, but I found that there’s just too much noise in there, too many things I wouldn’t use that make searching and finding the right records into a harder problem than it needs to be. I might provide a way to import an ingredient from that dataset into the database to save the hassle of typing the nutrition data in by hand, but for now it will all be manual.

I started putting together an editor with Druid’s widgets. This took some time - Druid has a rough learning curve, since it doesn’t work quite like any other GUI toolkit I’ve ever used. Rust has a lot of things that work well, but are not quite like anything else you’re used to, so Rust programmers will be familiar with that feeling. Still, I was able to get it working.

Building it raised a few user-experience questions.

How am I going to handle validating the data the user enters? It doesn’t make sense for an ingredient to carry ‘foobar’ calories. Druid has a component for that, but it doesn’t provide any visual feedback to the user to indicate that what they entered was invalid, let alone how or why. It’s not very user-friendly. I’ll probably have to build a widget for that myself.

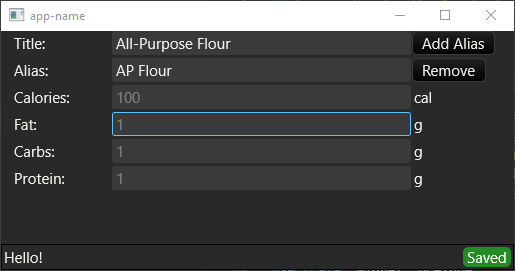

How am I going to save the data? When I’m cooking I won’t want to have to mouse over to the “Save” button and click it all the time, so auto-saving is a must. It would be nice to give the user some visual feedback about the state of their data too. So I built that little green indicator you see in the bottom-right corner - that’s a custom widget that toggles between Saved, Invalid (to indicate that the data is invalid in some way - it gives no further details yet), Failed (saving failed for some reason) and a little animated timer ticking down. Every time the user edits anything in the form, if the data is valid, it starts a three-second timer in the background and then saves the data if no new change is made in that time. It’s my first custom widget in Druid, and I’m actually pretty happy with how easy it was to build. In the process, I found and filed one bug report and I think I may have found a second one but I’m not sure. I’ve hooked up async-std to do the saving asynchronously, but that’s all - I haven’t actually implemented saving anything yet. Instead it just prints a message to stdout.

How am I going to handle errors? It’s always a possibility that writing my ingredient file to disk will fail for some reason, and the user should be notified if that happens. So far I don’t have a good solution to this; I’m using anyhow to handle errors but right now just printing them to stderr. I want to get this right before I move on to another editor because all of the editors will have to deal with this problem. They might as well share code.

Conclusion

I hope that was useful and/or interesting. I expect I’ll write more about Druid in later posts, but this one is getting long enough so I’ll leave it there for now.

I’d say I’ve gotten to this point with maybe 10-12 hours of active work since I started working on it on Thursday, Oct 1 (not counting the time I spent writing this post or building a test case for that bug report). Decent enough progress. I intend to make this a weekly thing, but next weekend is Thanksgiving weekend here in Canada. I expect I’ll be in a food coma and not interested in writing anything very much, so I guess the next post will probably be in two weeks. Cheers!

- I could keep a sqlite database in Dropbox as well, but that’s a recipe for irreconcilable conflicts and database corruption - sqlite quite reasonably isn’t designed for other programs to access its database files. I used to do exactly this with my RSS reader’s sqlite database, and every few months it would break and I’d have to use Dropbox to roll it back to the last working database file. [return]

- If you’re wondering, I don’t have any strong reason to prefer async-std over tokio (the other main async reactor in Rust), I just picked one. Hopefully it works out. I used tokio for my RSS reader and it works fine. [return]

- Incidentally, since I wrote that post, I’ve fully converted JARVIS (my RSS reader) into an HTTP server (using Rouille) and a WASM front-end that I can use in the browser (using Seed). Both are written in Rust, naturally. It uses nginx as a reverse proxy to serve the static front-end files and terminate HTTPS connections with a certificate provided by LetsEncrypt. Data storage is still handled by sqlite through Diesel. The server runs on an always-free tier Google Cloud VM with 512Mbyte of RAM and half of a virtual CPU and it is hilariously over-provisioned - I’ve tried to benchmark it for kicks, but I end up saturating my home internet connection before I hit 100% of that half-CPU - and that’s including compressing the responses and the HTTPS encryption overhead. Rust is pretty great. [return]