Hello! This post will likely be a bit shorter than the last. Today’s topic is a few thoughts about how complex it can be to parse human input, and how that interacts with Druid’s data model.

Progress

I think I’m nearly finished tweaking the ingredient editor. I’ve spent the better part of a month on just this one view and that might seem like overkill, but for software like this the user experience is the whole point so it’s important to get it right.

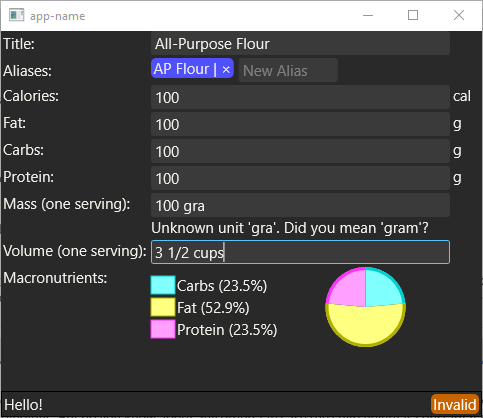

As you can see, the mass and volume fields are now much more lenient in what they accept. They handle fractions (including the unicode fraction characters), full singular and plural unit names, and even suggest a unit if the user mis-typed it. Additionally, I put together a simple pie-chart showing the calorie breakdown by macronutrient; this uses a pretty simple model behind the scenes but it should be sufficient. Though while I was writing this I realized that it’s not at all clear from the UI that it’s showing the percentage of the calories. I’ll have to fix that.

I’ve submitted a couple of pull requests to uom to enable the unit-parsing features I mentioned; one has been merged but the other hasn’t (yet) so I’m just working from a local clone of the uom repository. Thanks to the uom developers for their quick response to my pull requests. The “Did you mean $unit” suggestion is powered by strsim. I don’t really have much to say about strsim; I just dropped it in and it did the job with minimal trouble. That’s the highest praise I can give a library, I suppose. My code is using it in a rather inefficient way, but there are only a small number of unit strings to consider so that’s acceptable. I believe I’ll need to build a more efficient fuzzy-matching system for this project later on; when I do I might revisit this.

Behind the scenes, I’ve fixed a number of bugs and simplified some code. I was also able to update to the latest version of Druid. I complained in my last post that some changes had broken my code, but I was able to find an alternate way to implement what I wanted which actually worked out a lot better.

Druid’s Data Model

In my last post, I was complaining about how some work on Druid had broken my component for parsing user input and showing the errors. I’ve spent some time thinking about it, and came to a new understanding about how Druid sort of paints itself into a corner here. I’ll lay out the problem, the solution that the maintainers seem to be approaching, my own alternate solution and my reasons for taking a different path on this.

Let’s consider the following simple Druid code:

// Create a struct to serve as our data model

#[derive(Data, Lens)]

struct Model {

text: String,

number: Option<i32>

}

pub fn build_ui() -> impl Widget<Model> {

Flex::column()

// Create a textbox and bind it to the text field

.with_child(Textbox::new().lens(Model.text))

// Create another textbox and bind it to the number field,

// with parsing of the text the user enters

.with_child(Textbox::new().lens(Model.number).parse())

}

When the user types into the String text field, the text field of the model is changed

accordingly. Druid detects this change (that’s the purpose of the Data trait, which model derives)

and re-renders the UI. The same is true for the number text field, but it’s slightly different

because it needs to try to parse the user’s input into an integer.

A quick refresher on how Druid’s widgets work: Each widget contains its own configuration state, but is bound to a field in the data model. These fields can be any type that implements the Data trait, though individual widgets can add additional bounds or even specify that they only work with particular types. The Widget trait defines five functions that widgets implement; event, lifecycle, update, layout, and paint. Of these, update is the one relevant to us. To simplify a bit (read the docs for the full detail) the update function takes the new and old versions of the data and updates the internal state of the widget accordingly; for the textbox that would mean updating the text of the textbox and possibly recomputing some layout data. That way, when the paint function is called after the update is done, the textbox can render the new text.

Therefore, every keypress in either textbox results in a change that becomes an update call followed by a paint call.

The update function takes the new and old data as whatever type of field it would be bound to; for Textbox this would be string. As you can see in the code there is no string value for the number textbox to be bound to. In fact, that String lives in the Parse widget which wraps the regular textbox; the Parse widget forwards its own implementation of the Widget functions to the textbox as if it were bound to an external string. But that string is ephemeral - it can’t be accessed by the application. More importantly, every time the update function is called with changed data, the Parse widget must update its internal string by calling the Display formatter for the data type. So what happens if the display function returns a different string than what the user typed? Or, if the input cannot be parsed into an integer at all, then there is no integer to generate the new string from.

What can the textbox/parse code do here, except to overwrite that ephemeral string of user input with the string returned by formatting the new data? It tries to avoid clobbering the user’s input too badly, but there are limits to how well this approach can work, and in practice it does result in user-visible oddities. Consider - how would you type 500.000001 into a textbox if it parsed your input as 500.0f64 and formatted it to 500 after every keystroke? It wouldn’t be a good user experience at all.

To their credit, Druid’s developers are aware of this issue. The solution they seem to be aiming for is fairly straightforward. Instead of changing the backing data model on every keypress, we let the user type whatever they want. We don’t even try to parse it or update the backing model until the user presses enter or changes focus away to signal that they’re done, at which point the app will potentially change the string in the textbox.

I don’t really like this solution; it doesn’t work the way that users will expect textboxes to work, it means that other parts of the GUI can’t respond to changes in the text as the user types them and it still presents the possibility that it will noticeably change the user’s input. 1

After I thought about this problem for a while, I realized that it’s not just Druid that has a problem with data that can’t be round-tripped from string to structured form and back to the original string. What happens if the user enters some data and saves it (converting it to structured form in the process) then loads it from disk again? For simple numbers that’s probably fine - I wouldn’t remember how many trailing zeroes that I’d added after the decimal point. But what about masses and volumes? uom’s quantity structs don’t store the unit they were parsed from, but instead convert it to the appropriate SI base units and convert from that to whatever unit the programmer requests. I would be rather annoyed if I typed “1 pound” into a recipe and then came back to find it had been silently converted into “0.454kg”.

Once I realized all of this, the solution was quite obvious. Keep the string in the data model in addition to the structured form. The textbox can be bound to the string and update the structured form automatically with a lens. The String form can even be saved to disk without losing the user’s input; the structured form can be re-parsed on load if needed.

I’ve implemented that and it works exactly as expected.

This raises a tension that I had mentioned in the previous post as well - how intrusive should widgets be into the application’s data model? In my case, I want to be able to save the user’s text input as well as (or instead of) the structured form, so this is logically part of my data model anyway. Not every application will want that; should they be required to keep a string in their data model anyway to bind the textbox to, or should the textbox try to hide that as an implementation detail?

Parsing User Input

Humans are complicated. Of all the hairy problems that we have to deal with as programmers, many of the absolute hairiest crop up whenever our software intersects with humans. Text rendering, text editing, really just everything to do with text, time zones, names, addresses, recipes… the list could go on for a while.

Today, what I’m interested in is the complexity of parsing user input. In particular, user input that represents weights and measures (an area of stunning complexity in its own right). As I mentioned yesterday, it would be nice if recipes simply listed all ingredients by mass in grams. Needless to say, they don’t. Volume measurements - quarts, cups, tablespoons, teaspoons, ounces - are widely used, and when things are measured by mass it’s often done in strange foreign units like pounds or ounces 2 rather than grams.

On top of this, it’s impractical for people to measure volume with any precision without special equipment. I couldn’t easily measure out 0.44 cups with the stuff I have around the house. Instead, a set of basic fractions is available - I have a “1 cup” measuring cup, a “1⁄2 cup”, “1⁄3”, and so on. Measurements in recipes reflect this, sometimes calling for “1 1⁄4 oz” of something. So it needs to deal with fractions as well as decimals. Just to add a bit of extra fun, there are special Unicode symbols for some of the basic fractions. A lot of blogging software will automatically convert “1⁄2” to “½” when a recipe is published online, so it will need to be able to recognize those and handle them appropriately too, in case the user copy/pastes or I decide to add an import-from-web feature. 3

Since my recipe manager is also a nutritional calculator and calorie tracker, it will need to be able to do math on these quantities correctly. When I type in a cookie recipe using fractions and volumes and weird units, I expect it will sum up the calories and macronutrients in the specified quantity of each ingredient and divide by the number of cookies to estimate the nutrition of each cookie. That means I can’t escape having to parse this complexity.

Additionally, it would be nice if we could give the user a good error message to explain why their input couldn’t be understood.

Rust’s normal f64::from_str function fails at this pretty badly. It makes no attempt to handle

fractions of any sort, and the errors that it returns are designed for technical efficiency (small

stack size and no allocation) rather than human-friendliness. This isn’t a knock on the core

developers; they’re not trying to solve this problem, and it makes sense for a core error type

to be efficient; developers who want richer error information can add it themselves, but they

couldn’t remove it if core included it. Likewise, uom’s from_str code only handles regular

decimals as well.

So, I had to build my own layer on top, with custom parsing and custom errors. It passes every test

case I could think of, so I’m reasonably confident that it works, but it’s pretty hairy. I use a

pretty gnarly regex to detect whether the input contains a decimal number or a fraction (with

optional whole integer in front) and if it is a fraction, whether it uses the Unicode fraction

symbols or not. Following that, there’s branches to handle the different cases, parsing out the

numerator and denominator (or looking them up in a match for the fraction symbols), dividing out

the fraction and adding in the multiplier. Eventually it all resolves down to an f64 that I then

immediately substitute back into a new string along with the unit, in a format that uom’s from_str

can parse, so that it can handle the unit.

For errors, I used thiserror to generate an error type with nicer, human-friendly error messages. As you can see from the image above, this includes detecting when uom doesn’t understand the unit the user typed and suggesting a unit using strsim. It’s gnarly, but it works for all of the edge cases I could think of. I wish I could get away with being strict in what I accept, but one of the core design goals of this program is to present the minimum possible friction to the user, and forcing them to convert their fractional measurements into decimal just because that’s convenient for the programmer doesn’t fly.

As an aside, is there a way to interleave comments with raw strings in Rust? I don’t know of any, but it would be helpful for future readability if I could break up my gnarly regex into pieces and add a comment to explain each piece. That would be helpful to have.

Conclusion

OK, so it wasn’t that much shorter. I hope you found this interesting! I’m starting to think that weekly is a bit too much for these posts so I think I’ll go for every two weeks for the next one. See you then!

- It’s really frustrating when computers do that; it feels like fighting with the computer. Why, just this morning I saw somebody post a Wikipedia link that contained an apostrophe to a Discord server. Discord automatically rewrote the URL to use HTML entities instead - which broke the link on at least one user’s device. The poster tried to edit the link to restore the original apostrophe, but Discord applied the same transformation on the edit. I myself am frequently frustrated by well-meaning software converting “Criterion.rs” - the name of the benchmarking library I maintain - into a link, simply because it ends with “.rs”. [return]

- Yep, ounces again. They can represent either volume or mass; by convention “fluid ounces” refers to volume where plain “ounces” is mass, but not everyone follows this convention. [return]

- In fact, one of the tools that I’m building this recipe manager to replace gets this wrong and has done for years. It interprets “5¼ cups” as “51⁄4 cups” or 12.75 cups, rather than the correct 5.25. One of the many reasons I’m building my own alternative. [return]